By Eveline Gan, Writer

10-mins read

The recent revisions to the art syllabuses are set to transform the way art is taught and learnt in classrooms. For art teachers and students, this brings about both challenges and exciting opportunities. Central to the change is placing an emphasis on nurturing the learner’s personal voice, artistic growth and exploration.

Experts from the Arts Education Branch (AEB), Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board (SEAB) and Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) believe that the shift will empower students to embrace imperfection, have greater space to experiment, and ultimately, grow as artists. Here, they share their thoughts on what these changes mean for students and teachers.

Mr Larry Wong, Senior Assessment Specialist (Humanities & Aesthetics), Assessment Planning & Development Division, SEAB

During recent trials of the revised secondary school exam syllabus, Mr Larry Wong noticed a recurring pattern among students: when tasked to sketch their ideas, their paper was filled with erased lines and pencil rubbings. They all seemed hesitant to make mistakes.

“What struck me was that the majority of students feared putting a mark on paper unless it was the perfect stroke,” he recalled. “Every time they put something down on paper, they would erase it and when they made another line, sometimes over the same line they just erased. Very few students were comfortable and confident enough to trust their instincts and have fun.”

This fear of imperfection, Mr Wong believes, hinders the creative process and limits students from fully exploring their artistic potential. He believes that embracing mistakes and adapting are essential to creative growth – which the refreshed and revised syllabuses aim to address.

While polished, exam-specific finished pieces were the focus previously, the new portfolio paper emphasises students’ progress over time, showcasing how they conceptualise, develop and articulate their ideas. To do this, students – and their teachers – would have to trust themselves, take risks, and embrace the learning process.

“The ability to articulate and translate your thinking, thoughts, ideas on paper, screen or canvas is critical. You can’t keep erasing and expecting everything to be perfect each time,” Mr Wong said.

With the revised syllabuses, secondary school students will generate work throughout their day-to-day learning, from Secondary 3 to at least the first term of Secondary 4, Students will then select and curate materials from their study to compile into a portfolio and provide a written commentary of their learning. The new format provides a more holistic view of their creative journey. For teachers, this means adapting to a more open-ended, student-centred approach to assessment —a transition that Mr Wong sees as crucial for the long-term success of the curriculum.

“We hope that teachers can recognise that important learning happens in the classroom, and can be assessed at the exam level without the need for a separate exam-specific task,” he said.

To support teachers in helping students build this confidence, Mr Wong emphasised the importance of creating a safe and open classroom environment where students feel comfortable with experimenting and learning from mistakes. He also encouraged teachers to facilitate more peer discussions and critiques to help students see different perspectives and take feedback constructively.

“One of the drawbacks of the current exam format is that students show only their best work where everything is near perfect, glossy and super polished,” he said. “But there’s value in a student sharing a ‘horrible failure’, explaining what they’ve taken away from the process, and how the stumble hasn’t diminished them in any way. This portfolio approach allows them this space and opportunity.”

Mr Clifford Chua,

Academy Principal of STAR

Echoing Mr Wong’s emphasis on embracing the learning journey, Mr Clifford Chua said that the transition from coursework-based to portfolio-based assessment marks a bold shift not only in assessment methods; for teachers, it means rethinking the teaching and learning approach.

Recalling a workshop organised by STAR, Mr Chua shared how the participants - art teachers from various schools – were tasked with painting over irregular, ragged holes in dried leaves, with just five colours at their disposal. The result however, was unexpectedly stunning. “The leaves looked as if they were whole again because the colours matched so well,” he recalled.

This hands-on, experimental approach, Mr Chua believes, is emblematic of the kind of creative problem-solving and exploration the refreshed and revised art syllabuses aim to foster.

“As a teacher, when I look at the requirements of the portfolio, I must understand the rationale behind it: Why is MOE trying to assess our students artistic competencies in this manner? It is because we are trying to shift away from purely concentrating on the technical skills of the discipline, to look at the other equally, if not more important skills such as personal, voice, growth, experimentation, exploration,” he said.

Mr Chua said that the refreshed and revised art syllabuses open up more flexibility for teachers to adopt diverse pedagogical strategies that cater to students’ individual strengths and interests.

He encouraged teachers to approach drawing – one of the fundamental skillsets highlighted in the revised upper secondary syllabus – with a deeper appreciation for its complexity and versatility, and “not just to satisfy examination requirement”. Lessons could be structured and scaffolded to guide students through various learning experiences.

“For example, for a term module on developing observational skills, lessons might involve drawing exercises towards the use of pencil or charcoal to render a physical object and understand how form and structure can be articulated,” he said. “As a teacher, not only must I scaffold lessons to help students develop technical skills; how to manipulate their tools for shading and/or sculpting the forms they see but also, teach them how to see; how effects of light affect how form, shape and colour are perceived and experienced. This could apply to still life, portraiture, or whatever I choose to design for the students.”

Drawing can also simply be about mark-making where teachers could encourage students to experiment with various media. “Teachers could even try to see what marks clay – or even milk – can make. You’re not drawing for observation but for exploration and experimentation with materials and what is creatively possible. I imagine that it would be a fun and engaging way for students to learn, and I hope teachers will find it interesting to plan such lessons,” Mr Chua said.

He also called on Senior and Lead Teachers to take on more active roles in shaping the fraternity by sharing their expertise and experiences, ensuring a more vibrant, impactful arts education moving forward.

Highlighting the importance of art education in nurturing creative thinking and problemsolving skills—qualities that are valuable across all disciplines—Mr Chua has this message for art teachers:

I believe the arts will, in time, become one of the strengths of society. I urge you to recognise the significance of your work, not only within education but in shaping the minds of our young people.

”

Ms Jacelyn Kee Lee Ling, Deputy Director (Art & Dance), Arts Education Branch, Student Development Curriculum Division 2

As the rollout of the refreshed and revised Art Teaching and Learning syllabuses (TLSs) begins, one of the most telling responses to the transition has come from the teachers themselves. Over the 21 engagement sessions held between 2024 and 2025 to launch the secondary and pre-university Art TLSs, there was a clear sense of optimism, tempered with a dose of apprehension.

“Excited but anxious” was a common sentiment which Ms Jacelyn Kee observed among teachers during those sessions. “The anxiety here stems from a sense of duty and passion that Art teachers have for Art teaching, and their desire to implement the syllabuses well to benefit their students,” she explained.

Eager to brainstorm ideas and clarify how best to implement the revised syllabuses, some teachers expressed their interest to invite curriculum officers into their schools for consultations. Others formed self-initiated groups to discuss and share strategies for the transition. Their response highlights a key strength in Art education: “Our Art teachers are not change-adverse,” Ms Kee said. Despite the uncertainty, there is a deep commitment and passion to explore new ways of teaching.

Between 2024 and 2026, the rollout of eight new TLSs and seven exam syllabuses at the secondary and pre-university levels signifies a shift beyond traditional methods of instruction.

However, this does not mean that the core values of the old syllabuses have been sidelined. Ms Kee emphasised that much of what students and teachers treasure in the previous framework, such as self-expression, understanding the world through creative lens and cultural appreciation, has not only been preserved, but enhanced in ways that respond to a rapidly changing world.

For the secondary levels, the Core Learning Experiences (CLEs) introduce experiences unique to the learning of Art at each level, guiding students through a progressive learning journey. It’s not just about learning to make art; rather, the emphasis is on “shaping students habits and how they learn and think in Art, whether as artists or the audience”, explained Ms Kee.

For teachers already familiar with real-world creative practices, such as building portfolios, the refreshed and revised syllabuses may feel like a natural extension of their teaching. These teachers are likely to find the changes “exciting and empowering”, Ms Kee said.

At the same time, she acknowledged that some teachers might feel less comfortable with the open-ended nature of the revised syllabuses, and may need more time to adjust. This is particularly true for those who have traditionally focused on preparing students for national exams or relied heavily on drill-and-practice methods for technical skill development.

“Regardless of their starting points, teachers are likely to face practical challenges around how different student profiles may require thoughtful lesson design and greater scaffolding to access some of the learning experiences,” Ms Kee said. She added that queries from teachers, invitations for curriculum consultations or self-help groups are always welcomed.

Additionally, with greater student autonomy comes the responsibility for teachers to guide students in developing respect for creative expression and maintaining academic integrity.

To do this well, teachers will need to focus more on the learning process than just the outcomes, Ms Kee added. This involves revisiting their love for the subject, reflecting on how they themselves learned and were inspired.

For those who have not experienced some of the CLEs before, such as Art Journalling, she suggested trying them personally to better understand hurdles students might face and enacting some of the routines.

To teachers who are apprehensive about the transition, Ms Kee offered reassurance: “Have faith; when the learning is done well, the outcomes will naturally follow. With good follow through by teachers, teaching and learning of Art should be a process that is manageable, enjoyable and rewarding for both teachers and students.”

Here are some highlights, according to Ms Jacelyn Kee Lee Ling, Deputy Director (Art & Dance), Arts Education Branch, Student Development Curriculum Division 2

Encourage creative confidence and exploration:

In the Lower Secondary Art TLS, Making Thinking Visible through Drawing shifts the focus from the technical process of drawing realistically to using drawing as a way to explore ideas and make sense of the world.

Growth-oriented learning progression:

The concept of portfolios evolves across levels, from the use of a four-step process to structure learning at primary levels to considering the purpose, format and intended narrative for building portfolio for different contexts at the upper secondary and pre-university levels.

Room for personal expression and artistic voice:

Students have greater opportunities to explore personal interests and expression, whether experimenting with different art forms and media, responding to a visual stimulus or selecting artworks of interest

Critical thinking over drill and practice, memorisation:

Pre-university students no longer need to focus on remembering biographical and historical facts of artists from a prescribed list. Instead, they work on developing the ability to think critically, learn from artists and their art works, and to communicate their thoughts.

Discover how art teachers from Fairfield Methodist School (Secondary) integrate portfolio-based learning into a cardboard sculpture module, guiding students to document their creative journeys and develop self-directed learning skills.

Ms Desiree Tham Xue Ping

10-mins read

Ms Nurul Afia Mohammed Anuar Fairfield Methodist School (Secondary)

In today’s dynamic learning environment, fostering creativity and critical thinking is key to developing well-rounded students. In our newly revised syllabus, one powerful way to achieve this is through portfolio-based learning, where students actively engage in documenting and reflecting on their creative journeys. Here, we explore how a cardboard sculpture module, integrated with portfolio development, encourages students to reflect on their artistic process, build essential skills, and develop a deeper understanding of their creative growth.

In our Secondary 1 modules, we aim to help students develop routines for documenting their art-making processes. By using a common platform for reflections, research, planning, and feedback, students can build habits and basic organisational skills for effective collaboration.

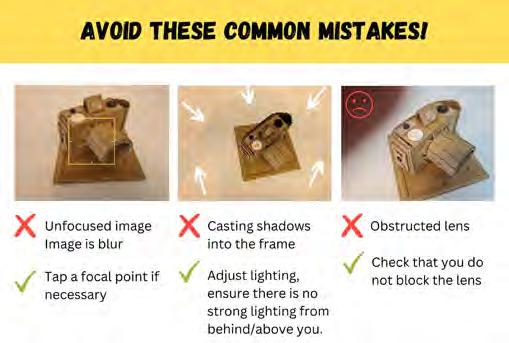

Caption 1: Besides documenting their processes, students also cultivate the habit of capturing good photos of their final works. Each art classroom has a documentation station with instructions.

Caption 2: The documentation station automatically guides students to our visual rubric, showing good and bad examples of work documentation. This helps save class time by eliminating the need to review the rubrics in detail during lessons.

To promote self-directed learning and reflection, students are required to spend 10 minutes each week identifying their challenges on Padlet. This routine helps them assess their progress and enables teachers to provide feedback more efficiently.

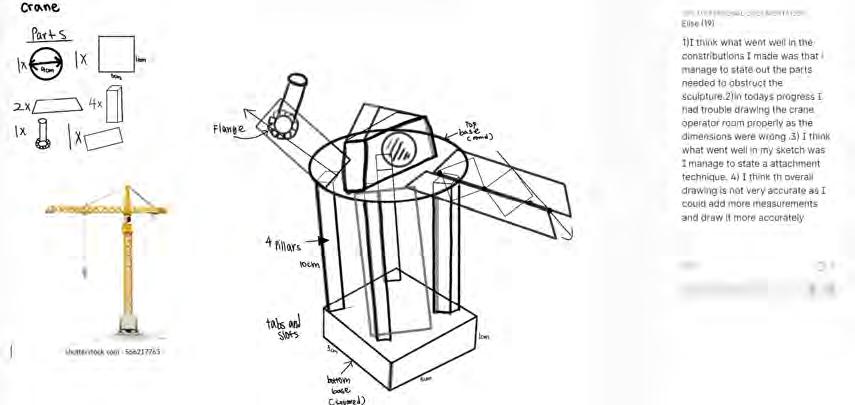

Caption 5: Using the same skills they pick up in Term 3, students now focus on developing research skills and finding new ways to present their cardboard sculpture from the theme “Then & Now”.

Caption 3: Students develop a habit of reflecting on their mistakes and challenges during the art-making process, guided by teacher-provided question prompts.

Caption 4: Teachers’ weekly feedback helps students with self-assessment and promotes selfdirected learning, as students automatically refer to the Padlet for feedback and reflection.

The cardboard sculpture module is divided into two main projects over one semester. In the first project, students learn assembling techniques and the ideation process to create a cardboard machine. In the second project, they independently apply these skills to an Elegant art task integrated with history.

At the beginning of each project, students conveyed their sculptural ideas through ideation drawings using a 2-point perspective to depict their sculptures in 3D form. To make their thinking visible, students have to ensure they had a clear plan for constructing their sculptures, these sketches included dimensions, cut-out drawings of each component, and labels for attachment techniques.

In the second part of the module, students took a selfdirected approach, using historical references from migrant workers in Singapore learned in History lessons. Working in pairs, they documented their process in a digital portfolio on Google Slides, including relevant images, ideation sketches, and progress photos to organised their art processes.

On Padlet, students reflected weekly on their challenges and improvements, sharing progress and contributions to track their creative journey. They evaluated their learning by responding to guided questions and teacher’s feedback, allowing them to recall, observe connections, and assess their growth throughout the process.

“Using portfolios significantly enhances students’ critical thinking throughout their art-making process. It subtly encourages them to curate their research thoughtfully and articulate their reflections, guiding them to consider how best to present their creative journey and insights. This reflective practice fosters deeper engagement and intentionality in their work.”

- Ms Desiree Tham

“Using this inquiry-based learning approach, students make their thinking visible by presenting their creative journey of this module through scaffolded documentation of ideation and process as well as reflection at key points in their learning journey. This enriching experience has nurtured their ability to be reflective and curious problem solvers, fostering skills that will support their self-directed learning in the future.”

- Ms Nurul Afia

“Web-based platforms (such as Padlet, Google Classroom, etc) allow classmates and teachers to easily share ideas and receive feedback. These platforms also allow us to include images we find online and store them on Google Slides. Sketchbooks and hard copies lack the convenience and flexibility that online tools provide, such as being able to edit, share and organise large amounts of information easily.”

- Ashley Sec 1E

“The theme ‘Then and Now’ shows the contrast between items or things that people used in the past compared to the more advanced things we use now. The project also helps us to learn more about Singapore’s history through the artistic expression of art.”

- Ethan Sec 1A

“Working with 3D materials was fun. The different attachment techniques helped me to properly construct the cardboard sculpture. I learnt to experiment and problem-solve while having fun. I felt that the whole process was enjoyable, and the art-making process taught me a lot more about art.”

- Gracie Sec 1A

How can students become better communicators and team players? Ms Mehrun Nisha from Gongshang Primary shares how she and her team designed collaborative learning experiences based on the refreshed Primary School art syllabus.

Ms Mehru Nisha

Gongshang Primary School

10-mins read

“Great things in business are never done by one person. They’re done by a team of people.” – Steve Jobs

These wise words from Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple who revolutionised digital technology, remind us that success is rarely achieved alone. His emphasis on teamwork highlights the power of collaboration. Similarly, I was thrilled to see that the refreshed Art syllabus offers exciting possibilities to develop students’ 21st Century Competencies, collaboration being one of them.

As Head of Department (HOD), I believe that teachers should have a shared vision when planning the school’s art curriculum. While we know the desired syllabus learning outcomes, it is also important to contextualise the curriculum to meet the needs of our student profiles. At Gongshang Primary School, we noticed that while our students take pride in their work, we wish they would show more empathy and appreciation of others.

Traditional art assignments foster creativity and self-expression, but they can sometimes lead students to become overly possessive of their ideas. How can we help students become better communicators and team players? To address this, my team and I began designing collaborative projects for the refreshed syllabus.

Setting up a large-scale exhibition can seem overwhelming. So how can teachers design memorable learning experiences based on the refreshed syllabus? Together, We Can Achieve Anything

3: Art Teachers showing support for the largescale project. The life-sized crocodile was created by Art Teacher, Mr Scott Lai (AYH, internal). Art teachers: Mr Hazmi (ST Art, internal) & Mdm Mehrun Nisha (HOD PAM)

We introduced our students to the Exhibition in Curriculum core learning experience through a Mangrove Exhibition on Earth Day. The topic centred around conservation, and Primary 3 and 4 students created artworks for the exhibition.

Primary 3 students were introduced to Tan Zi Xi’s Plastic Ocean and Han Sai Por’s Black Forest, and they collaborated to create sea creatures using repurposed and recycled materials.

Meanwhile, the Primary 4 students collaboratively crafted ‘hybrid’ creatures, using papier-mâché, inspired by notions of adaptation. Art Club students, led by Mr Scott Lai, also contributed by creating creatures for the mangrove habitat using papiermâché. The centrepiece was a life-sized crocodile.

We began our planning in November 2023 and the shared sense of mission kept us motivated! The Mangrove Exhibition turned out unexpectedly interactive and was a visually impactful, unforgettable experience.

6: Special shoutout to Mr Azhari, Science Teacher, for the props (oars and life jacket) which enhanced the visually impactful experience

Collaborative projects are not easy to pull off. In our school, teachers of the same subject meet regularly for professional learning. Providing just-in-time solutions to classroom concerns and sharing ideas on-the-go do not have the same impact as having a meeting with a focused agenda and specific deliverables. These meetings ensure progression of learning and consistency in assessing learning across the cohort and levels.

When educators leverage on our strengths, we can create a dynamic and robust curriculum. We implemented all that we set out to do, navigating challenges with creativity, even launching a digital package. This was possible because we dedicated time to discuss and develop strategies for anticipated problems. The Art Department did not work alone. We had support from beyond our department, such as the HOD ICT and Science Department. Collaborative, multidisciplinary efforts among educators enhance students’ learning experience.

Primary 3 student, Joel said,

“It is fun to work in groups as we can help each other out. The recycled project was fun as we got to express our creativity and also help to recycle materials at the same time.”

When asked if he would like to do more group work in the future, he replied,

“Yes! I would like to do more group work. I had a lot of fun working with my classmates.”

Primary 4 student Estelle added,

“I loved the way we did the hybrid dragon as a group.”

I encourage fellow educators to come together, pool their efforts and share resources to create their own collaborative art projects for the refreshed syllabus. We are our students’ best role models in teaching effective communication and collaboration. I assure you; the journey is both satisfying and rewarding.

Mr Michael Ee Wei Wen from St Joseph’s Institution shares tried-and-tested tips on how to enhance drawing experiences in the classroom.

Mr Michael Ee Wei Wen

St Joseph’s Institution

10-mins read

I never thought I could draw. Having failed aptitude tests for elective art programmes, I often felt less capable as an art student throughout my younger years.

While these tests help teachers assess a student’s readiness, they might unintentionally reinforce stigmas around one’s drawing ability. Now, as a teacher, I stand by drawing as a fundamental experience that helps students gain deeper understanding of their hands, mind and their drawing tool.

The revised secondary school syllabus has placed drawing as a core learning experience in our curriculum, and rightfully so, as it remains one of the most immediate ways to translate ideas into reality on paper. While modern derivations such as the Apple Pencil or Wacom stylus open up possibilities for drawing, there remains a world of exploration to be uncovered with the humble graphite pencil or charcoal stick in hand.

Drawing is a personal act of expressing one’s relationship with first, oneself, and then, with the reality one experiences. Here are some studio tips that I practise to this day, which I hope will be useful for the drawing experiences you create in your studio spaces:

Tired of teaching with grids but still want to help students grasp form? Get the paper dirty - literally. Smear it with charcoal powder from top to bottom, and invite students to draw what they see through subtraction. While cut or kneadable erasers can work for this, there’s nothing quite like shifting charcoal with a chamois cloth. They can easily be found on Shopee at a fraction of the cost and in larger sizes, making them very affordable and good for sharing when cut into smaller cloths.

Caption 1: The Drawing NLC, which I participated in in 2023, gave me opportunities to draw alongside other educators – a professional development endeavour I highly encourage!

L: Caption 2: Mark Heng, Year 4 Josephian Arts Programme (2021), working with a chamois cloth and charcoal powder at the school field.

R: Caption 3: Mark Heng’s A2-sized term assessment drawing using charcoal and graphite.

L: Caption 4: Subtractive drawing by Yuto Hayashi, Year 1 Josephian Arts Programme (2020)

R: Caption 5: Subtractive drawing by Liyu Jiong Yang, Year 1 Josephian Arts Programme (2020)

While we are often taken by the precision of proportionate accuracy in realistic line drawings, achieving it is an uphill task that many struggle with. It was only much later in art school that I learnt the power of squinting while drawing. This simple gesture allows one to easily assess the lightest light and the darkest dark in one’s set-up. With squinting practice, the drawer develops the skill to identify where these extreme ends fall on the tonal scale, enabling dimensionality to be sculpted on paper.

L: Caption 6: Subtractive drawing by Kyler Ong, Year 1 General Art Programme

R: Caption 7: Sow Hao Yuan, Year 1 General Art Programme (2023), learning to see highlights and shadows through squinting during his still life observation lessons.

My strictest drawing teacher enforced this rule for half a semester while we were introduced to line drawing. Those six weeks of eight-hour drawing lessons were painful, but the experience taught me about the possibilities of depth that could be created with the thinnest of lines. What emerged was also a newfound respect for Rembrandt’s drawings, which showed how movement and weight could be conveyed with a single line. Years later, I recreated the same experience for my students at St. Anthony’s Canossian Secondary and St. Joseph’s Institution. Journeying with them through the struggle was rewarding and fulfilling.

L: Caption 8: A selfmade quick sketch using line and slight tone to understand form, weight and the gesture of the body.

Elaine Scarry’s excerpt from On Beauty encapsulates the essence of drawing: “What is the felt experience of cognition at the moment one stands in the presence of a beautiful boy or flower or bird? It seems to incite, even to require, the act of replication. Wittengenstein says that when the eye sees something beautiful, the hand wants to draw it.”

At the heart of our discipline lies a thirst for beauty, and drawing brings us closer to it through observation. While advanced illustrators can conjure tight and freeform drawings from memory and imagination, it is their years of observational practice that have honed their technical proficiency. As art educators, our studio time with students is an opportunity to invite closer observation of the beautiful world we live in, one drawing at a time.

R: Caption 9: Rembrandt’s Standing Man with a Tall Hat and Stick (1629) is just one of the many amazing line drawings that show his sensitive line control to create forms that have both weight and a sense of ground. (Source)

Ms Samantha Lee Yuping from Bukit Panjang Government High School shares how she brought lessons in fashion design to life by taking students on an immersive learning journey through Orchard Road.

Ms Samantha Lee Yuping

Bukit Panjang Government High School

10-mins read

As part of my efforts to incorporate aspects of the revised syllabus, I was particularly keen on creating an out-of-class opportunity for design immersion.

For context, the plan was to introduce fashion design to my Secondary 3 G1 art students, and the aspect I focused mostly on in class was Avant-garde fashion design. Using the art inquiry model, the in-class activity focused on investigation and making. My students were tasked with sifting through various imagery and visuals in different types of fashion, then experimenting with art elements and principles to create an exciting avant-garde design.

Caption 1: Students working on their avant-garde fashion collage using recycled magazines and materials they brought to school, focusing on experimenting with shapes, colour and visual texture.

After creating their designs, the students reflected on their work and that of their peers, curating a fashion collection that promoted dialogue and sparked design conversations.

This flow led to discussions about fashion brands, their seasonal collections and how the fashion industry markets its lines.

From

Caption 3: Students giving peer feedback and assessing one another’s work based on observable use of formal art elements.

Caption 4: In groups, students observed and discussed the different designs and their characteristics, curating a fashion collection and sharing their insights with the class.

We then took our learning outside the classroom. On a learning journey to Orchard Road, my students took in the fashion store displays from Ion to Takashimaya. It was a chance for them to observe fashion branding and marketing, and look at fashion from a more commercial, real-world perspective.

Sure, avant-garde fashion may seem more exciting visually and narratively but the commercial fashion industry, which includes household brands like Uniqlo or higherend brands like Gucci and Louis Vuitton, was already known to my students through TikTok and other social media platforms. Tapping into what they were already familiar with from their everyday social media consumption allowed me to draw meaningful connections to their learning.

The students were tasked with photographing the stores and their displays, analysing the use of art elements and design principles, and making comparisons between the different brands.

We stopped in front of certain brand stores to dissect their visuals or compare them to their neighbour’s displays. I facilitated the discussions by asking guiding questions –for instance, about the use of colour, lighting, space, the fonts used for the logos, and even the type of uniforms worn by the employees – because every element had to come together to form the brand’s identity. Once my students got started, they were quick to pick up on what they were seeing and began linking it back to concepts of visual impact and marketing strategies.

By the end of our two-hour learning journey, my students might not have remembered all the appropriate art terminology, but they were able to recognise and categorise some visual styles and marketing strategies that brands use. For example, they noted how the use of more negative space between the items on shelves conveyed exclusivity, or how using contrast in logos and store colours attracts attention.

As we moved from store to store, I realised that my students were practising; observing a visual stimulus, analysing its formal properties, making comparisons and repeating the process at the next store. Along the way, they built a sense of inquiry around the formal elements used and design choices made by actual designers, honing their visual literacy skills and applying them.

I could have achieved something similar using a worksheet with photos of storefronts or projected images in the classroom, but the experience of walking through the mall, choosing which stores they liked and wanted to discuss, made the learning experience more immersive and impactful.

Wandering through an environment where most people do not necessarily think of “design”, my students saw how the concepts they learnt in class are applied everywhere, literally in each store and figuratively throughout the fashion industry. To me, that was a learning experience well worth the effort, offering my students a hands-on immersion into the real-world application of design.

Caption 6:

(Left) Comparing the visual impact of two neighbouring stores; analysing the different logos, fonts, colours applied, and how they each grab the consumers’ attention in their own way.

(Right) Discussing the contrasting colours, arrangement layout and use of space in a storefront display.

5-mins read

Ms Arnewaty Binte Abdul Sokor Greenridge Primary School

My journey into the Arts began in arts management. After over a decade in arts management and as a practising artist, I felt drawn to a more impactful role where I could support children. It all began during my vacations spent at seaside villages. I bonded with the local children there.

Although we didn’t share a common language, I used drawings to communicate with them. The experience left me reflecting: How could I use art to make a difference in a child’s life?

To me, being an art teacher means transforming a child’s perspective of the world. Through Art, children can develop a richer, more nuanced understanding of themselves and the world. Art also fosters relationships, building connections with the world around them.

One memorable experience was helping my Primary 4 students draw proper human figures. The assignment topic was ‘My Family’ under the theme ‘People and Places’. Many expressed their struggles, saying things like, “Ms. Arne, I can only draw stick people”, “Can we not draw people?”.

Drawing is one of the fundamentals in art making. For that unit, I taught my students a simplified method of overlaying basic shapes on a stick figure, starting with the torso, followed by the arms, hands, legs and finally, the feet. The result was a huge improvement, and the students felt proud that they could draw their family members as proper human figures. Most importantly, they gained confidence and started to believe in themselves.

A challenge I encountered was ensuring the safety of Primary 1 students in the art room. Six-year-olds have varied developmental levels and motor skills. This can lead to disparities in learning abilities and pacing, and affect their ability to use art supplies safely and effectively. During lessons, I enforced consistent routines and used positive reinforcement, which ensured safety, fostered better behaviour and strengthened the structured environment in the art room.

Ultimately, my goal as an art teacher is to challenge traditional art appreciation, encourage critical thinking about visual culture and guide my students towards different ways of seeing. After all, there is so much more to art than simply creating pieces.

5-mins read

Ms Khoo Lih Yui

St Andrew’s Junior College

“ ”

It’s hard to get a job with an Art Degree. You probably became a teacher only because you couldn’t find other jobs, right?

This comment from my former art students reflects how hegemonic schools of thought still persist among some learners. I, too, once held such pragmatic views in my formative school years. However, art education encouraged me to take ownership of my learning and re-evaluate my views on the role of art in society.

As a medium that both shapes and reflects our lived experiences, it is important for students to recognise the intrinsic value of art in everyday contexts. A notable challenge I’ve faced in class is students’ limited and preconceived views on artmaking, where the focus is often placed on producing “polished” outcomes. Olivia Gude suggests that learning should be a fluid and deeply personal process of play (Gude, 2017). Building on this notion of play, I hope to foster attitudes of curiosity, inquiry and experimentation through art education.

Informed by my background in anthropology and its theory of Reflexivity, my teaching methods largely focus on student autonomy and guided inquiry. The implementation of open-ended projects, museum visits and artist-run workshops has provided students with exposure to diverse practices and encouraged them to critically examine socio-cultural contexts embedded in works of art they study and create.

Coupled with teaching relevant skills and contemporary art knowledge to stay attuned to current trends, these experiences aim to develop students’ metacognition and visual literacy skills to effectively interpret, evaluate and communicate visual texts.

Through these experiences, I have seen students create artworks that surpass initial task requirements, experimenting with new mediums and ideas that resulted in more personal and expressive outcomes. Watching them explore new perspectives and venture beyond their comfort zones has reaffirmed my belief in the power of play in artmaking.

Reference Gude, O. (2017). Principles of Possibility: Considerations for a 21st-Century Art & Culture Curriculum. Art Education, Vol. 60, No. 1, 6-17.

5-mins read

Ms Yew Ning Fuhua Secondary School

When I read the article on “Artistic Collaborations within School” in July 2024 issue of STAR Post (Art), I felt a surge of excitement. The way the article highlights the integration of Art with other subjects truly struck a chord with me. It demonstrates how interdisciplinary learning can go beyond traditional curricula, transforming education in meaningful ways. This approach resonates deeply with me because I believe that Art isn’t just a standalone subject—it’s a bridge that connects diverse fields of knowledge, equipping students with skills for real-world applications, much like how Art functions in the modern world.

An area I am passionate about is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Art education. At Fuhua Secondary School, students are exploring AI tools like Art Breeder in their art lessons, but not before thoughtfully addressing the ethical considerations involved. There is so much potential here, but it is crucial that we navigate these ethical challenges carefully. I would love to contribute to more discussions around AI in Art education, as it could open up exciting new avenues for both educators and students alike.

What I appreciate most about the STAR publication is how it encourages educators to embrace a wider array of pedagogies and ideas, drawing inspiration from the collective experiences of other educators. It serves as a safe, inspiring space where educators can exchange ideas, share tips and explore new possibilities together. For upcoming publications, I am eager to see more discussions on how educators are addressing sustainability in the Art classroom.

Encouraging eco-friendly art projects that teach students about sustainability, recycling and the environmental impact is more important than ever. This is a pressing issue that demands our attention, and I believe it’s crucial to equip the next generation with the knowledge and design thinking necessary to create responsibly.

Khaliq Officer (Art)

Rafeeza_Khaliq@moe.gov.sg

Vivian Loh Lai Kuen

Master Teacher (Art) Vivian_LOH@moe.gov.sg

Chun Wee San

Master Teacher (Art) CHUN_Wee_San@moe.gov.sg

Silvia lim Academy Officer (Art) Silvia_LIM@moe.gov.sg

Han Zi Rui Senior Assistant Director (Art) HAN_Zi_Rui@moe.gov.sg

https://star.moe.edu.sg/ +65 6664 1496

2 Malan Road, Blk P

Singapore 109433

Tel: +65 6664 1561

Fax: +65 6273 9048

Published by the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR)